When developers think about accessibility, the conversation usually revolves around screen readers, semantic HTML, color contrast, or keyboard navigation. And all of these are very important.

But there’s a less-discussed area you should consider: how your site behaves without JavaScript.

Here’s what we’ll cover:

- Reasons JavaScript can fail

- Progressive Enhancement in Practice

- When a page absolutely Requires JavaScript

- Conclusion

Reasons JavaScript Can Fail

In a world where nearly every site relies on JavaScript frameworks for rendering and interactivity, it might sound “irrelevant” to consider the “no-JS” experience. But JavaScript can fail for many reasons. For example:

- Slow or unstable networks: Mobile users in low-bandwidth regions might experience timeouts or incomplete script loading.

- Browser extensions and blockers: Security or privacy tools can block or strip scripts.

- Assistive technology limitations: Some users browse with JavaScript disabled, or with legacy/specialized browsers (or strict enterprise/campus policies) that block scripts.

It’s easy to assume JavaScript is always available, but it’s definitely not guaranteed. Users will face an unnecessary barrier if JavaScript fails. We can’t always predict why it might fail, but we can prepare our websites to fail more gracefully.

Testing your site without JavaScript is about improving resilience and accessibility.

Progressive Enhancement in Practice

Using JavaScript, you might be tempted to write something like this:

<span onclick="goToPage('/homepage')">Home page</span>But <span> isn’t a link, isn’t keyboard-focusable by default, and it won’t work if JavaScript is disabled. Instead, you should use semantic HTML that works by default and enhance it only when JS is available:

<!-- Works with or without JS, and is announced as a link by assistive tech -->

<a href="/homepage" id="home-link">Home page</a>

<script>

// Progressive enhancement: only intercept if JS loads

const link = document.getElementById('home-link');

link?.addEventListener('click', (e) => {

// If you have client-side routing, uncomment to prevent full page reload:

// e.preventDefault();

// router.push('/homepage'); // or history.pushState(...), etc.

});

</script>This way, users get a real link and keyboard accessibility by default, and your SPA routing (or other enhancements) kicks in only when scripts are running.

A submit button only works without JS if it’s inside a <form> with a real action (and server-side handling/validation). For example:

<form action="/contact" method="post" novalidate>

<label>Message <textarea name="message" required></textarea></label>

<button type="submit">Send</button>

</form>Note that without JS, built-in browser validation may be limited – so make sure you always do server-side validation in a case like this.

When a Page Absolutely Requires JavaScript

Not every feature can be delivered without JavaScript. Complex web apps may rely on scripts to function.

In these cases, we can create a simple page that informs the user why the page is broken.

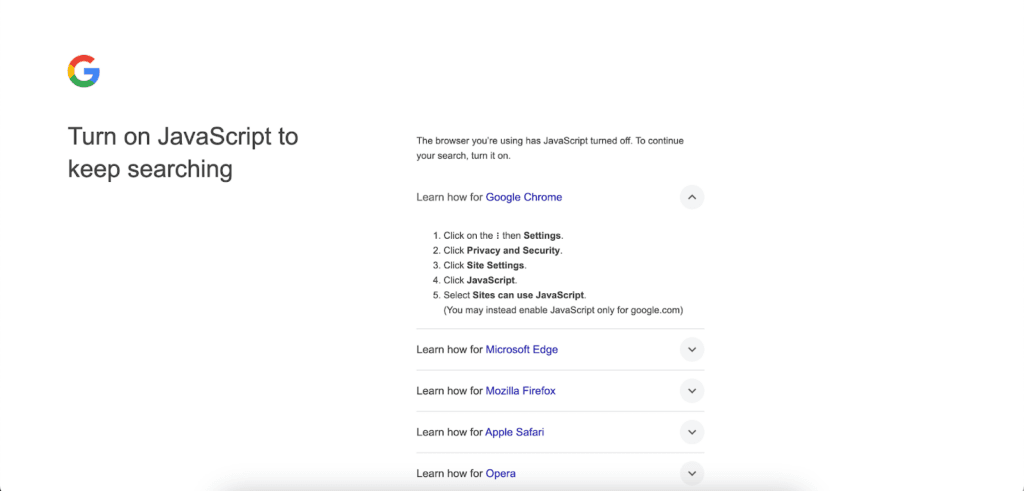

A great real world example of this would be Google’s no JavaScript page. If you disable JavaScript in Chrome and navigate to Google, you will see a page that informs the user that they need to turn their JavaScript on in order to access the page.

Instead of leaving users staring at a blank page when scripts fail, Google is informing the user why they can’t access the page. Just note that Google’s message appears when JavaScript is disabled. If JS merely fails to load, a <noscript> message won’t appear (more on this in a second).

A “no JavaScript” page like Google or a simple message like “Loading interactive dashboard (requires JavaScript)” is much more accessible than silence. You can include a fallback message inside a <noscript> tag that explains why the page requires JavaScript and what users can do. Here’s an example:

<noscript>

<p>This page requires JavaScript to function properly. Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.</p>

</noscript>But <noscript> has a key limitation: it only renders when scripting is disabled in the browser. It doesn’t help when scripts are enabled but fail to load or crash at runtime (like from a CDN outage, CSP block, MIME/type=module mismatch, or syntax error).

To handle such cases, you can use server-rendered HTML or content-first templates so the page still shows something meaningful even if hydration/JS fails.

By adding fallbacks, you ensure that users aren’t left wondering whether the site is broken. Even when JavaScript is essential, you can still make the experience accessible by acknowledging the dependency and offering alternatives.

Conclusion

Testing without JavaScript isn’t about supporting every possible edge case. It’s about building resilient, accessible, and inclusive websites.

- Users with unreliable connections benefit from fallback content.

- Everyone benefits from predictable, reliable experiences when scripts fail.

Accessibility is about reducing barriers wherever they appear. And sometimes, the biggest barrier is assuming JavaScript will always work.